Hip-Hop has been a part of my life since forever – and forever is a long, long time.

I was born in the summer of 1970. At the age of four, I was placed in the foster home of a mother with five children, three of whom were adults – their children older than me. The other two – “Manchilds” still living at home. My brothers (for that’s what they became and still are, though one has since passed away) were Five Percenters. If you don’t know what that is, take a trip down the Google Rabbit Hole. I guarantee, it’ll be a fascinating read.

By five, I wanted to tag along with my big brothers, who were God-like to me. In fact, they were Gods. Bakeem and Tuma – their God names, not their government-issued monikers – were part of a generation from which Hip-Hop was fully birthed. I would sit meekly tucked in a corner, eyes wide, ears perked, listening to their banter, a language molded and shaped by fear, and anger, and resentment, and rebellion, and a refusal to simply disappear out of sight. These two young men contributed to my foundation, a foundation steeped in questioning and analyzing and, of course, dropping mad science. At six and seven years old, I could spit today’s Mathematics, but struggled with multiplication and division. I wanted to be an Earth like their girlfriends – wrap my head in beautifully-colored scarves, don a nose ring accentuating a beauty denied no more, and be surrounded by burgeoning Gods sworn to protect their Earths at all cost.

My brothers were often tasked with babysitting. Let me tell you what a treat that was. They’d reluctantly drag me along with them to the park to meet up with friends, all of whom happened to be part of the Five Percent Nation and many of whom were also fine as hell. I soon developed a crush on one in particular – Father Divine (Oooh, Daddy). Divine, whose government name was Melvin – if I remember correctly – was Puerto Rican and also a foster child (I’ve still got a thing for Puerto Ricans – ask my hubby). In addition to mastering the supreme mathematics and alphabets, they’d blast music. Earth Wind and Fire, Kool & The Gang, Parliament, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, People’s Choice, LaBelle, The Emotions, Funkadelic, The Main Ingredient, Deniece Williams, Marvin Gaye, James Brown, and the playlist goes on and on and on and on.

1977. The Blackout that changed the face of music. I remember that night vividly. I’m from East New York, Brooklyn. I’d spend my summers hanging on the block, in front of my house – maybe a few doors down if my mother wasn’t watching – playing skelly, hopscotch, steal the bacon, kick the can, dodge ball, stick ball, stoop ball, but, mostly, jumping double dutch, even in 95 degree weather. If someone got hold of an industrial-sized wrench, on went the Johnny Pump. I was not supposed to play in the middle of the street or, God forbid, get my hair wet. Inevitably, some older boy from the neighborhood would snatch me up, carry me in his arms, and walk us directly in front of the full force of New York City water gushing into the streets, flowing down along the gutters before disappearing into the sewer drains, of which our handballs were constantly being swallowed. The night the lights went out was both exciting and scary as hell. I was quickly ushered inside, where I was stuck watching what I could barely make out from my bedroom window above. When I emerged the next day, my street no longer looked like my street. It looked as if my neighborhood had been demolished and burned to the ground. It would never be the same again. But same is not always better, for there is no progress without movement.

And, yet, out of the ashes, Hip-Hop was born. My brother, Tuma, who had moved – along with his girlfriend and newborn son – from Medina to The Desert, would bring me to their home on weekends. His girlfriend, Tamisha – his Earth – continued my schooling by dragging me along with her to summer jams in the park. Now, I’m not talking some gentrified, plush-and-greenery joint. I’m talking those school yards in the hood, with broken and crumbling asphalt or concrete, chain-linked fences missing entire sections, and nothing ever growing no matter what might be buried beneath the surface. The music, blasting, could be heard blocks and blocks away. The crowds – thick, sweaty, and… I don’t know, maybe representing everything Hip-Hop is supposed to be. We were there together, allowing the music to wash over us, drench us in life, an affirmation that we were still here. Still breathing and kicking and stirring up all the shit needed to get us through the next day and the next and the next and all the days after.

Tuma soon abandoned The Five Percent Nation for The Nation of Islam. Willing to follow my big brother just about anywhere, I, too, became a junior member of the MGT/GCC (Muslim Girl in Training/General Civilization Class). Bakeem, well, that’s his story to tell, not mine. However, our stories are forever connected, and the journey and path his life took continue to shape the woman I am today. For a period of time, these two brothers were separated and, although they’d be reunited, life doesn’t promise us forever. So, I spent my preteen and teenage years in the shadow of my brother, clinging to the words of Minister Louis Farrakhan. I lived for Saturdays at Mosque No. 7C, for I made it onto the drill team. My crisp white or blue or beige uniform, my strong-heeled shoes, and a rhythm reverberating through my legs and arms as I marched across that room above the furniture store on Utica Avenue and Eastern Parkway. It wasn’t long before I started calling drills. Left flank march. Right flank march. A call and response, quite similar to the ones found in the music of the streets, and among the congregations familiar to those of us who know. You know what I’m saying.

1982. Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five stepped on the scene. The Message. The words embedded in my soul. Don’t push me cause I’m close to the edge, pushed me closer to a path of discovering who I was, or who I was to become. Twelve years old, knock-kneed, flat-chested, but voiceless – possibly on mute.

1983. One year later, thirteen and fear closing in tightly. But, for one summer, one amazingly freeing summer, Run-DMC lit the scene. Sucker M.C.’s filled every crack and crevice in Brooklyn, in Queens, in The Bronx, Harlem and, I suppose, even Staten Island, where the Gods of all Gods would later emerge – Wu-Tang is definitely for the children. My knuckle and wrist seesawing to the beat. I memorized every word, every line. I sat at the lunch table with the boys who tried to mimic this new form of word play, dissing one another and their mamas in the process, exercising a voice that would no longer be contained.

1984. My life turned upside down. An older guy. An ex-con, recently released, set his eyes, his hands and his fangs on me. My fourteen-year-old-screams, ricocheting throughout an apartment filled with boisterous laughter. I begged. I pleaded. I clawed. I screamed until my voice no longer belonged to me. The days, the weeks, the months, the years that followed, plunged me deeper into a darkness from which I thought I’d never emerge. Not even music would push me to the surface.

Then came the summer of 1987. Seventeen. As the old school mamas would say – I started smelling myself. I began dating the bad boy in school. He’d been suspended for throwing a chair at a teacher and, of course, he’d been a former Five Percenter turned Sunni Muslim. Oh, and he was dealing drugs and selling guns, as well. I felt safe and protected with him, despite the obvious dangers his lifestyle placed us in. Having attempted suicide just the year before, I’d permanently moved into the Linden Houses projects with my big brother and his family. PTSD is real, and can have you spiraling out of control. I was on a path headed straight to my grave – one way or another. But, then, music reentered my life. Music that spoke to me. Told me I wasn’t alone. That year, Eric B and Rakim shook the hell out of me. Paid in Full was my nourishment. I got a question as serious as cancer… Is Rakim a God or what? Yet another Five Percenter. Guide you out of triple stage darkness… That he did, that he did.

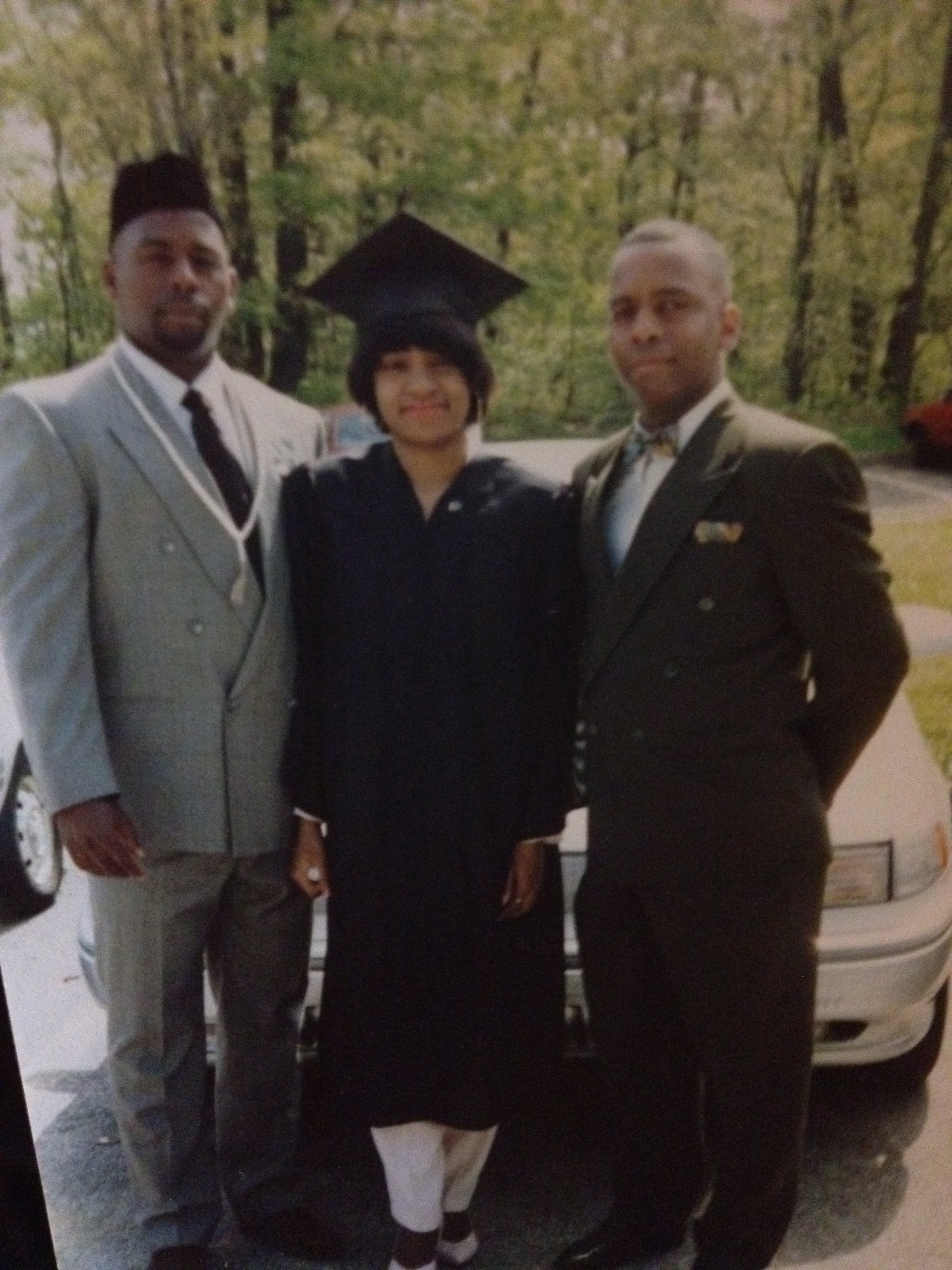

1988. The golden year of Hip-Hop. MC Lyte, Salt-n-Pepper, Queen Latifah (Wrath of My Madness), P.E., Slick Rick, MC Shan, Big Daddy Kane, Eric B. and Rakim, Boogie Down Productions, EPMD, Jungle Brothers, Biz Markie, Dougie Fresh, Chubb Rock, and on, and on, and on, ’til the break of dawn. Sorry, East Coast girl here. You can take the girl out of Brooklyn, BUT YOU CAN NEVER TAKE THE GIRL OUT OF BROOKLYN. At eighteen, I knew something had to change, or I’d be dead by the end of that year. I ran away – to college. I wasn’t necessarily seeking an education; I was seeking safety, shelter. I left a lot behind, but never, ever, ever would I abandon Hip-Hop.

While 48 years spent living in the rays of Hip-Hop has given me life and voice and a foundation from which to draw, I’ve slowed down a bit. I don’t know many of today’s artists and, quite frankly, have forgotten some from yester-years. What I do know – what I will always know – Hop-Hop continues to run thick throughout my veins, and pumps life into the heart and soul of everything that I am.